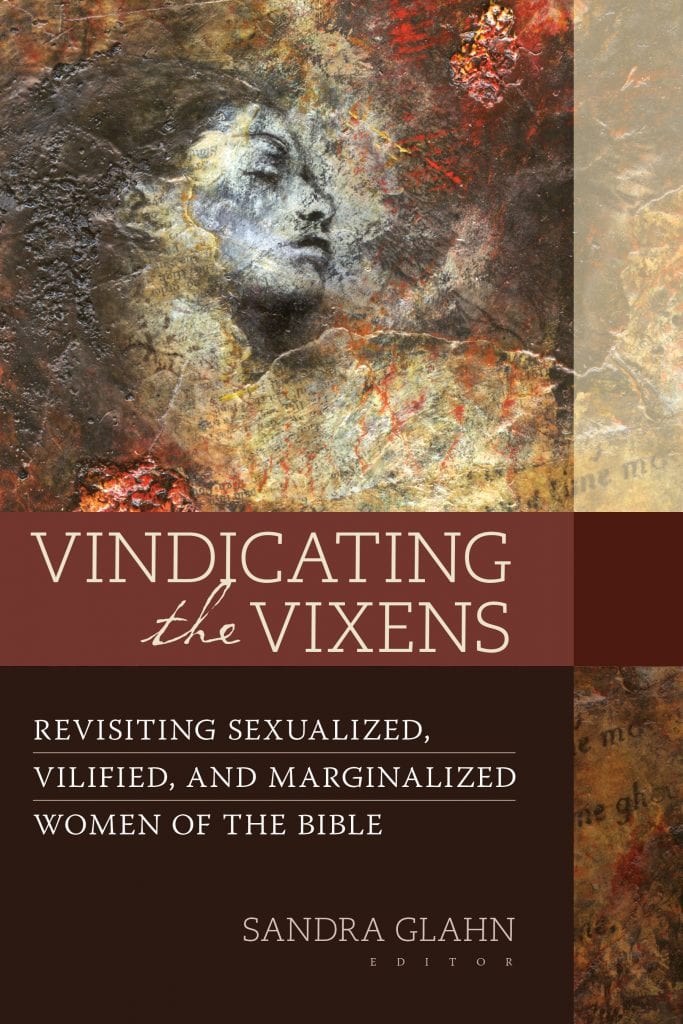

Bathsheba, Tamar, Rahab, Hagar, and the Samaritan woman at the well—were they really the “bad girls” of the Bible or simply women whose situations were greatly misunderstood? In Vindicating the Vixens: Revisiting Sexualized, Vilified, and Marginalized Women of the Bible (Kregel Academic), sixteen writers, alongside general editor Sandra Glahn, take a closer look at the stories of these and other prominent women to help readers gain a better

understanding of these women’s God-given roles in the biblical narrative. The church has a long history of viewing notable women of the Bible through a skewed interpretive lens. For example, Eve is best known for causing the fall, Sarah is blamed for tensions in the Middle East, Ruth acted scandalously on the threshing floor, and Mary Magdalene is infamous for a life of prostitution. But do these common representations accurately reflect what Scripture says about these women of the Bible?

Part 1 of an interview with Sandra Glahn, Editor of Vindicating the Vixens

Bathsheba, Tamar, Rahab, Hagar, and the Samaritan woman at the well—were they really the “bad girls” of the Bible or simply women whose situations were greatly misunderstood? In Vindicating the Vixens: Revisiting Sexualized, Vilified, and Marginalized Women of the Bible (Kregel Academic), sixteen writers, alongside general editor Sandra Glahn, take a closer look at the stories of these and other prominent women to help readers gain a better understanding of these women’s God-given roles in the biblical narrative.

The church has a long history of viewing notable women of the Bible through a skewed interpretive lens. For example, Eve is best known for causing the fall and Mary Magdalene is infamous for a life of prostitution. But do these common representations accurately reflect what Scripture says about these women of the Bible?

Q: Vindicating the Vixens is a collaboration written by an international team of scholars. How did the concept and execution of the book come together?

Vindicating the Vixens has been on my heart and mind for more than a decade. When I served as editor-in-chief of Dallas Theological Seminary’s magazine for seventeen years, I became acquainted with the writing and research of men and women from a cross-section of multiple societies who brought perspectives to some biblical stories that seemed truer to the original than what is typically taught in the West. Then, as I studied history and ancient cultural backgrounds at the doctoral level, I ended up revisiting some of our western-influenced interpretations such as marriage practices in the ancient Near East. The woman Jesus met at the well in Samaria would not have dumped five husbands. More likely, she had been widowed many times.

As I revisited some Bible stories such as this one and as I read the works of others who had done similar work, I wanted to bring all this research together in one place and include a variety of ethnicities and backgrounds.

Q: Some women in the Bible most certainly fall into the category of “bad girls.” How do those women differ from the ones discussed in the book?

Right! Our goal is not to vindicate women who did evil—such as Jezebel who lied and had someone killed over property or Potiphar’s wife who tried to seduce Joseph and left him stuck in jail. We are looking at women wrongly vilified. Take Bathsheba, for example. There is nothing in the text that even suggests she consented to physical contact with David and certainly not that they “had an affair,” as some claim. The text says she was washing herself—and that word “washing” could mean she was washing her hands. What we know about power differentials also suggests that when we consider a king’s authority over the wife of one of his soldiers, we need to stop making Bathsheba responsible. That is not how the author of the story tells it. The text says David saw her washing and sent for her—sent men, plural, for her.

What happens when we blame her instead of placing the responsibility where the author does? We can end up with the idea (prominent in many churches) that women are the temptresses; we can teach that it’s a woman’s job to keep a man from falling, that men are helpless and controlled by their passions so women must cover up, be hidden, and take responsibility for men’s actions. What an insult to men! We women are called to love our brothers, but we are not called to take responsibility for their actions.

Q: When discussing the genealogy of Jesus as outlined in Matthew 1, it’s not uncommon to point out the few women included and refer to their sordid pasts. Why do we have the tendency to focus on the negatives of their history, especially when the men in the bloodline had as many flaws as the women?

Jesus’s genealogy in Matthew is full of both male and female sinners, but the women’s sinfulness is not the point Matthew is making. Not all of the women in Jesus’s line had sordid pasts, and in making their sex lives our focus, we miss what the author is telling his Jewish readers. In the highly stylized genealogy in Matthew’s Gospel, every person is intentional, with Jesus’s ancestors arranged into three groups of fourteen generations. Matthew makes a break from the usual exclusion of women from genealogies, and he’s clearly up to something. In his Gospel, foreign kings worship Jesus at his birth. Later a centurion—a Roman soldier—requests healing for his servant, and the text says this centurion “amazes” Jesus with his faith. Jesus grants the request and tells the disciples, “I have not found anyone in Israel with such great faith.” Notice “not anyone in Israel.” Matthew salts his narrative with the faith of Gentiles. In the genealogies, Matthew is setting up his readers, the Jewish faithful, to accept cultural and racial outsiders into the community of faith through belief, not blood.

Judah married the Gentile Tamar. Bathsheba is the wife of a Hittite. Rahab is a Caananite. Ruth is a Moabite. These are outsiders who are women of faith in the Messianic line. Judah says of Tamar, “You’re the righteous one, not I.” Rahab says she believes in Yahweh Adonai as Elohim. Ruth says Naomi’s God will be her God. Bathsheba suffers a great injustice but is grafted into the royal line. The idea of Gentiles being included would have blown the minds of Matthew’s readers, but that was the promise God had made to Abraham—that through him all nations would be blessed.

Q: Throughout the past couple of months, the news has reported story after story of women coming forward, sharing their experiences of sexual harassment and abuse from men in a position of power. What similarities might their stories have with someone such as Bathsheba?

Sarah Bowler, the person who wrote the chapter on Bathsheba, said of her that understanding her tale has ramifications for how Christians respond to a world saturated with sexual misconduct. She wrote, “As I researched, I found current examples in which Christian writers and editors failed to be empathetic toward victims as they reported stories. Even sadder, some spiritual leaders rape or sexually abuse young women, and many of the victims still receive partial blame in situations where a spiritual leader is fully at fault.

“It really hit home for me after a pastor’s kid I had discipled several years ago started reading [my writing] about Bathsheba. She got back in touch to say: ‘Thank you. I was raped two years ago Friday on a date in my home. I had three ministry leaders whom I held on a pedestal put full blame on me. . . . I can never thank you enough for not blaming the victim.’ How we interpret biblical narratives affects how we interpret events around us. When we say phrases such as ‘Bathsheba bathed naked on a roof,’ we overlook the fact that Bathsheba was an innocent victim. We may also forget the modern-day Bathshebas. I long for the day when believers eradicate the line of thinking in which the victim shares partial blame for a perpetrator’s sin. One step toward that end is sharing the true Bathsheba story.”